Google just wrapped up defending itself against a forced breakup of its advertising empire. But here’s the twist nobody saw coming: splitting up the company might actually hurt the publishers it’s supposed to help.

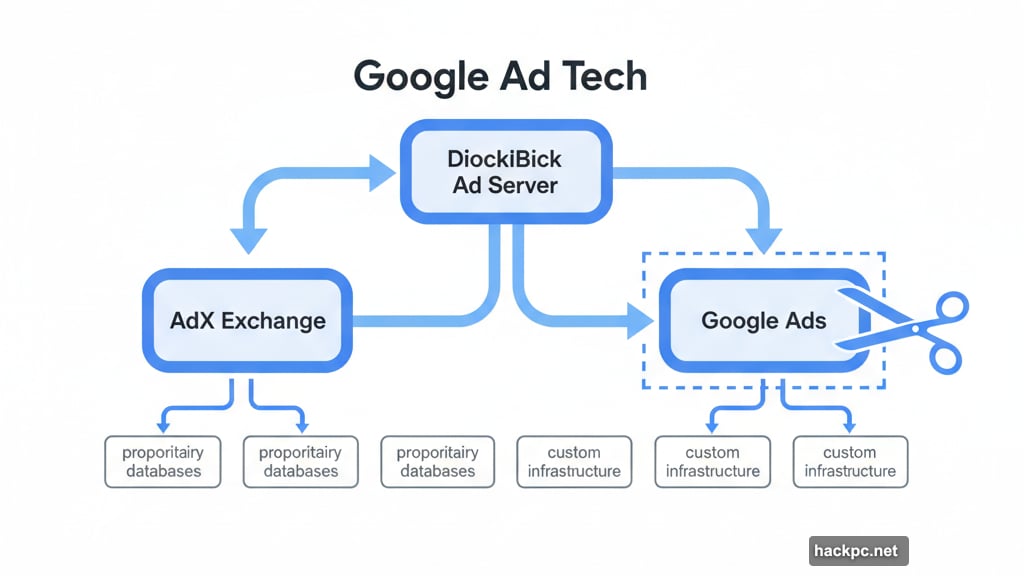

The Justice Department wants Google to sell its AdX exchange and open source parts of its DoubleClick ad server. Sounds straightforward. But Google spent this week explaining why it’s more like dismantling a nuclear reactor while it’s still running.

Federal Judge Leonie Brinkema already ruled Google illegally monopolized two key advertising markets. Now she faces a tougher question: what punishment actually fixes the problem without creating new ones?

Why Breaking Up Google Isn’t Simple

Google’s defense boiled down to one message: this is way harder than it looks.

Glenn Berntson, Google’s Ad Manager Engineering Director, put it bluntly. Even the simplest version of breaking up Google’s ad tech tools is “a massive undertaking.” He compared it to space travel: “Going to the moon is simpler than going to Mars.”

That’s not just corporate hyperbole. Google’s ad tech systems rely on proprietary infrastructure built over decades. Plus, they connect to Google’s other services in ways that aren’t easy to untangle.

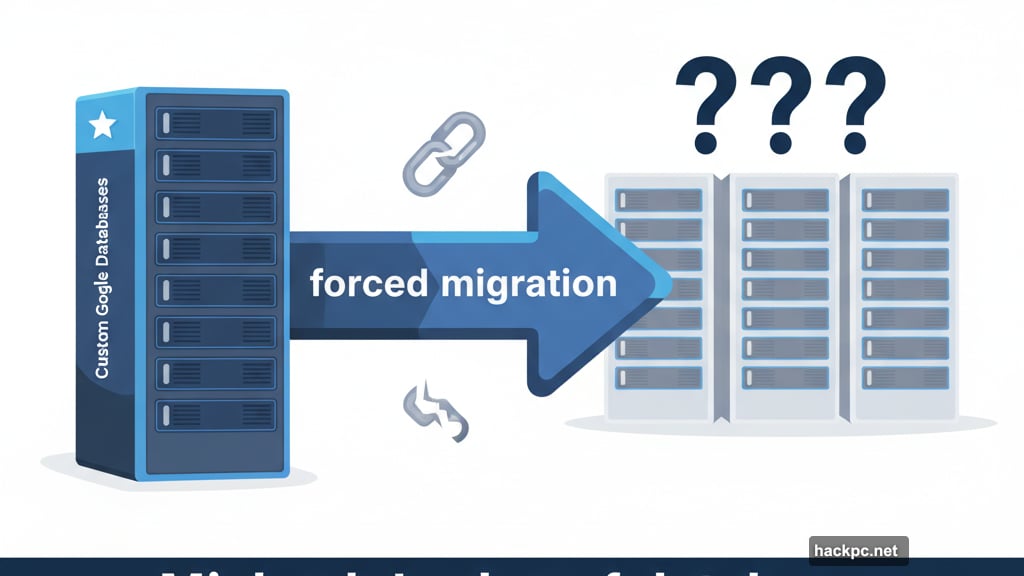

Jason Nieh, Google’s technical expert, explained the database problem. Google’s ad systems use custom databases designed specifically for their needs. Replacing them means finding alternatives that don’t exist yet. “We’re trying to replace the Michael Jordan of databases,” he testified. “There’s only one Michael Jordan, and he’s irreplaceable.”

Here’s what Google says makes a breakup so complex:

The technical systems are deeply interconnected. Google employees might quit rather than work for a new AdX owner. And customers could face service disruptions during the transition.

What Google Offers Instead

Google proposed a different approach: behavioral restrictions instead of forced sales.

Tim Craycroft, a Google ad tech executive, even suggested new concessions on the spot. Google would formally commit not to integrate its buying tools directly into DoubleClick for Publishers. That sounds helpful.

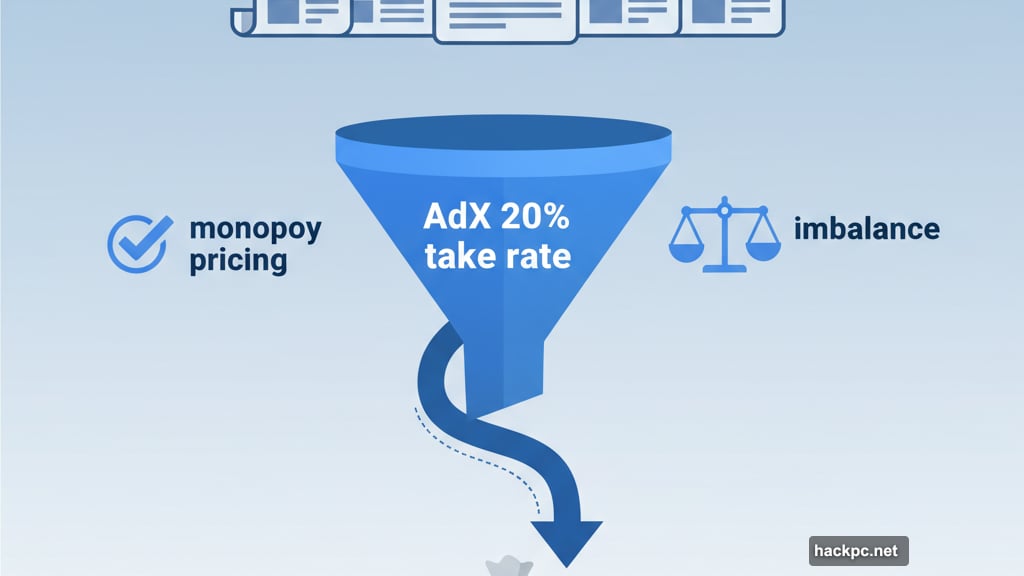

But Brinkema pressed on other points. Would Google lower AdX’s 20 percent take rate, which the court already ruled was monopolistically high? Craycroft wouldn’t commit.

Moreover, Google won’t agree to ban practices it claims not to use. For instance, Google says it doesn’t use data from YouTube or Search to power its ad tech business. Yet it wants that option available for future competition.

Google’s economic expert Andres Lerner even argued the company shouldn’t have to give up its monopoly power entirely. Instead, it should just stop using that power unfairly. Brinkema spotted the contradiction immediately. “I see a tension there,” she responded.

The Real Risk for Publishers

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: Google might be right about some of this.

Rajeev Goel, CEO of rival ad exchange PubMatic, explained the challenge. Sure, Google would probably comply with a court order. But writing that order is the hard part.

The order needs to prevent not just Google’s current anticompetitive behavior, but every possible way Google might recreate its dominance in the future. That’s nearly impossible to predict.

When PubMatic reported technical issues to Google, Goel couldn’t tell if delays were legitimate or intentional. Was Google actually working on fixes? Or deliberately slow-walking solutions to keep more money for itself? Without transparency, publishers can’t know.

So behavioral remedies might fail because Google could simply find new ways to advantage itself. Meanwhile, forced divestiture might fail because the technical complexity creates service disruptions that hurt publishers even more.

Mixed Signals from the Judge

Brinkema sent conflicting messages throughout the trial about which way she’s leaning.

She acknowledged the historical example of AT&T’s breakup. That split accelerated cell phone development. But it also destroyed Bell Labs, one of history’s most productive research institutions. “That’s what people comment on,” she noted.

Yet later, she seemed more receptive to the Justice Department’s argument. When discussing potential remedies, she said “talking about conduct really isn’t important” compared to preventing Google from regaining dominance.

The DOJ used a visual aid showing multiple roads all leading back to a box labeled “Monopoly” with Google’s logo. The point: Google could route around behavioral restrictions to rebuild its market power through different methods. Brinkema joked about needing game tokens and houses to complete the Monopoly theme.

Still, her questions revealed genuine uncertainty about the right approach.

The Two Elephants Nobody Mentions

Brinkema raised what she called “two elephants in the room” that might matter more than technical arguments.

First, whatever remedy she orders becomes legally binding. Google faces contempt of court charges if it refuses compliance. That’s serious leverage for behavioral restrictions.

Second, Google already faces multiple antitrust lawsuits and will likely face more. Maybe the sheer volume of legal pressure changes the company’s behavior regardless of specific remedies.

But that second point assumes Google learns from these experiences. The evidence suggests otherwise. Google continued monopolistic practices in ad tech even while facing the Search case that ultimately went against it.

What Actually Happens Next

The trial wrapped up this week. Brinkema will eventually issue her ruling on remedies.

Google beat a breakup order in the Search case. Now it’s trying for two in a row. The company argues behavioral changes plus market pressure from lawsuits will restore competition without the risks of forced divestiture.

Publishers caught in the middle face an uncomfortable choice. Keep dealing with Google’s monopoly under behavioral restrictions that might not work. Or hope a forced breakup doesn’t crater the advertising systems they depend on for revenue.

Neither option looks great. But doing nothing isn’t an option either, since Brinkema already ruled Google’s conduct was illegal. Something has to change.

The question is whether the cure ends up worse than the disease. We’ll find out when Brinkema makes her call.

Comments (0)