A familiar voice on public radio might be powering Google’s AI podcast tool. At least, that’s what one well-known broadcaster is alleging in court.

David Greene, former host of NPR’s Morning Edition and current host of KCRW’s Left, Right & Center, has sued Google and its parent company Alphabet in California Superior Court. His claim? That Google took his voice without permission and used it to train NotebookLM’s Audio Overviews feature.

What Is NotebookLM’s Audio Overview Feature?

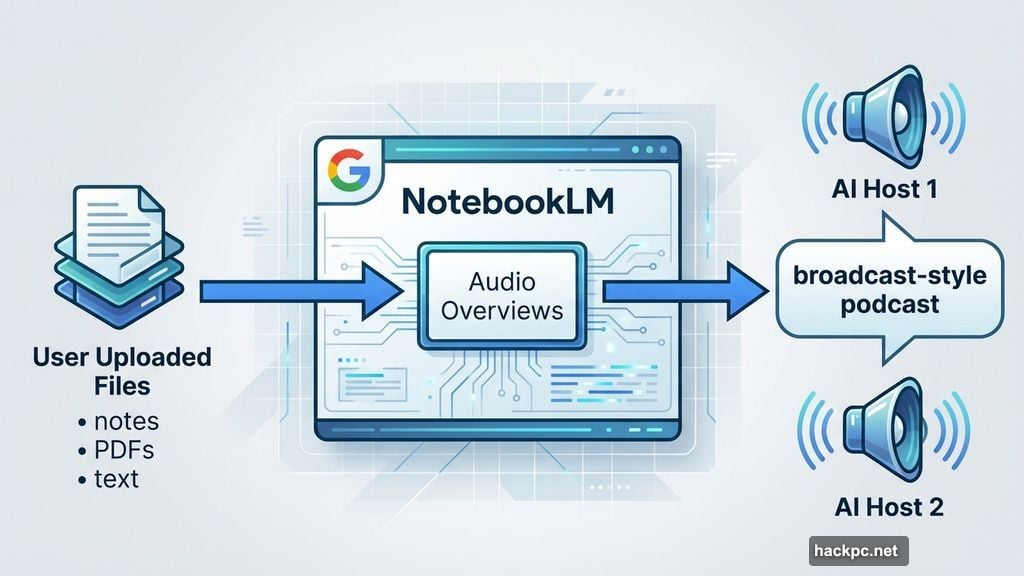

NotebookLM is Google’s AI-powered research assistant. You feed it documents, notes, or files, and it generates insights from that material. But in fall 2024, Google added something particularly interesting: Audio Overviews.

This feature lets users generate an AI-hosted podcast based on whatever information they upload. Two AI voices discuss the content in a conversational, broadcast-style format. It sounds polished. And according to Greene, it sounds a little too familiar.

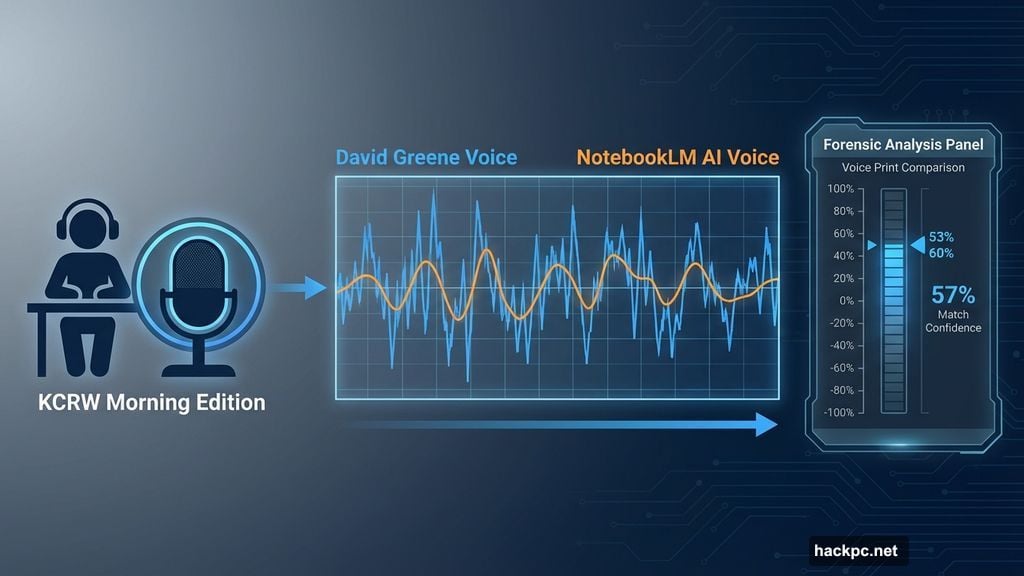

Friends and listeners began reaching out to him after the feature launched, telling him that one of the podcast voices sounded remarkably like his. Greene took that seriously enough to hire an independent forensic software company that specializes in voice recognition.

What the Voice Analysis Found

The results landed somewhere in the middle. The forensic firm compared Greene’s voice to the NotebookLM host voice and found a confidence rating of 53% to 60% on a scale of -100% to 100% that his voice was used to train the software.

That’s not a slam-dunk result. But it was enough for Greene to move forward with the lawsuit. The filing alleges that “Google used Mr. Greene’s voice without authorization and then used those stolen copies to develop, train, and refine its AI broadcasting product, NotebookLM.”

Google pushed back quickly and firmly. “These allegations are baseless,” a Google spokesperson told CNET. “The sound of the male voice in NotebookLM’s Audio Overviews is based on a paid professional actor Google hired.”

So far, Google has not publicly identified the voice actor it claims to have used.

AI Voice Rights Are Becoming a Real Legal Battleground

!Digital waveform visualization showing AI voice analysis comparison between two audio recordings

This case fits into a growing wave of legal and ethical disputes over AI-generated voices. And it’s not the first time a high-profile name has raised concerns about their voice being copied without consent.

In 2024, actress Scarlett Johansson went public with concerns that an OpenAI voice assistant sounded strikingly similar to hers. OpenAI pulled the voice in question shortly after the controversy went public.

Meanwhile, the industry is also seeing legitimate licensing deals emerge. Last year, ElevenLabs struck agreements with celebrities including Matthew McConaughey and Michael Caine to use their voices in AI-generated audio. That approach puts consent and compensation front and center.

The Greene lawsuit highlights a tension that’s only going to intensify. AI tools that generate audio and video content need voices to sound human and engaging. But the line between inspiration and imitation, or between training data and theft, remains genuinely blurry from a legal standpoint.

Why This Case Matters Beyond One Lawsuit

This isn’t just about David Greene and Google. It’s a test case for how courts will treat voice data in AI development.

Right now, there are no clear federal rules in the United States governing how AI companies can use recorded voices for training purposes. Several states have passed or are considering legislation, but national standards lag far behind the technology. So lawsuits like this one become the proving ground.

For broadcasters, voice actors, and anyone whose voice is their livelihood, the outcome here carries serious weight. If courts rule that AI companies can freely train on publicly available audio without compensation or consent, that fundamentally changes the value of a professional voice. On the other hand, if companies must license every voice used in training data, the economics of AI audio tools shift dramatically.

Google’s position is straightforward: they paid a professional actor and did everything right. Greene’s position is equally clear: his voice ended up in the product without his knowledge or payment.

Someone is right. And eventually, a court will have to figure out which one.

Comments (0)